Violence has many faces.

- Afro Toned

- Apr 13, 2022

- 4 min read

The recently concluded exhibition, Njabala; This is not how, piqued my interest in revisiting the story of Njabala as told to us when we were younger.

From memory, I could only remember a folk song which was often sang; and the vague allusion to a ghost doing chores on behalf of Njabala, the main character in this folk tale.

Reading this version more recently, more so after visiting the Njabala exhibition left me with a tension and heaviness unfamiliar.

Sarah Nansubuga’s performance piece; Wake with Me, is an exploration of the metaphorical loss of cultural identity, through the literal loss of a family member, and the journey through storytelling to preserve and reclaim what is lost using the folklore Nsangi and the Ogre. Nansubuga’s performance sets the scene for the rest of the exhibition as the work challenges us to wrangle with how culture has been practised, what we have come to understand it as; and what we are propelling it to become.

Specific to this exhibition, we are confronted with womanhood and the baseline expectations of womanness in this society.

Pamela Enyonu’s work, Stella’s Goat, is a direct critique on society (patriarchy)’s obsession with virginity. From childhood, girls are taught to preserve themselves for marriage, inculcating into them, us, the belief that it is only in marriage that this that is considered precious is gifted away to a life long partner. It is even more strange that the girls are not expected to ask questions around this virginity and even to speak of it again.

There are several challenges to this narrative; the first one being that, when this gift is robbed from you, who do you run to? Exactly, nobody, because after all, it is a secret.

The second being that while boys are not necessarily encouraged to preserve their virginity, but in fact encouraged to explore (with sisters of others), they are in the end rewarded with the fattest and shiniest, most precious thing that we have attached value to; virginity.

Enyonu’s work cited, more specifically makes reference to the Buganda practice of a husband-to-be gifting the bride-to-be’s brother with a goat, in appreciation for preserving the sister’s virginity if said bride is indeed proven to be a virgin.

So, what is virginity, how is it preserved, and how do we assess its value or lack thereof?

Related to this is Sandra Suubi’s performance piece, Samba Gown. This is a re-imagination of a bride’s walk down a church aisle, except, this is happening on one of the busiest streets of Kampala. The performance shows a woman on her wedding day, waking up early in excitement and getting ready as culture would have it, and as passers-by and traders look on and often break into laughter. As she starts the long journey down the aisle, along the way, we see words written onto her dress, household materials that she needs to use in the home are also pegged on to her gown. Throughout the performance, the bride is presented as jovial.

Suubi uses the wedding gown, made from sacks, as a living archive of the experiences of women who were interviewed about expectations before marriage and their findings after.

Esteri Tebandeke, in her short film, Little Black Dress, expounds on Suubi’s work. It explores an issue many find within the constraints of marriage, but often keep silent about. Tensions rise between a couple struggling with infertility. The film aims to topple the notion that men cannot be the reason for infertility amongst couples seeking to conceive.

This story is not new. Ayobami Adebayo, in her book, Stay With Me (2017), explores similar issues in modern Nigeria when main characters Akin and Yedije struggle with infertility and it is later revealed that Akin, the husband was, infact, impotent but coarsed his brother into impregnating his wife, Yedije who later lost two children to Sickle Cell Anaemia. In both stories, women bear the responsibility for fertility and infertility as though conception is achieved in solitude. In both stories, the husbands knew about their diagnosis, and without telling their wives, they orchestrated solutions in the form of fertility medication, in the case of Dee, the main character in Little Black Dress, and a “sperm donor” for Yedije in Stay With Me.

Violence shapeshifts amidst silence.

Immy Mali, in her installation, Lord, invites us into the uncomfortable silence after sexual abuse. Lord is a wooden bed frame, carrying a naked mattress, holding razor blades. Presented together with Silence in Dance, a 5 minute video, this mixed media installation is a reflection of our inherent reluctance to talk about sexual abuse, because, the perpetrators of such kinds of violence are recipients of goats, after all.

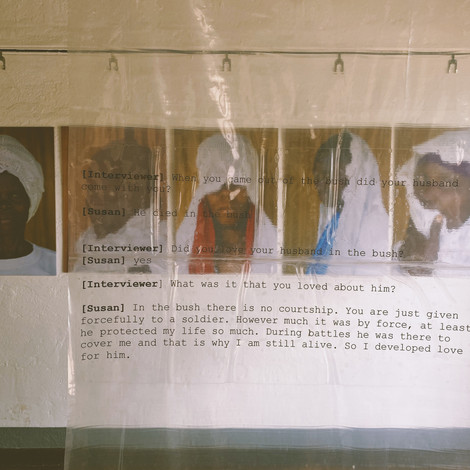

Silence, a photo story by Miriam Watsemba seeks to break this cycle by sharing the stories of women who have suffered physical and sexual abuse in intimate relationships. Sharing is not only empowering, but also liberating, more so for survivors of abuse.

So where do we go to unpack this physical, physiological, and psychological violence against us? Where do we find healing? Where do we go from here?

From the former forced wives of LRA combatants as portrayed in Kanyo, a photo series by Bathsheba Okwenje, we learn that there is life after trauma suffered; that there is still love to be felt and love to be given. Most importantly, we learn that in the end, we still belong to ourselves and as such we must do the work of saving ourselves.

Perhaps we could start by rewriting (retelling) Njabala; from a perspective that is all inclusive, teaching boys and girls about belonging, about humanness, about this land and our collective responsibility towards it.

Can we agree that this is the starting point to develop and reframe what makes us feel anchored?

Njabala This is Not How is an invitation to talk openly, to heal collectively and to learn from one another.

Comments